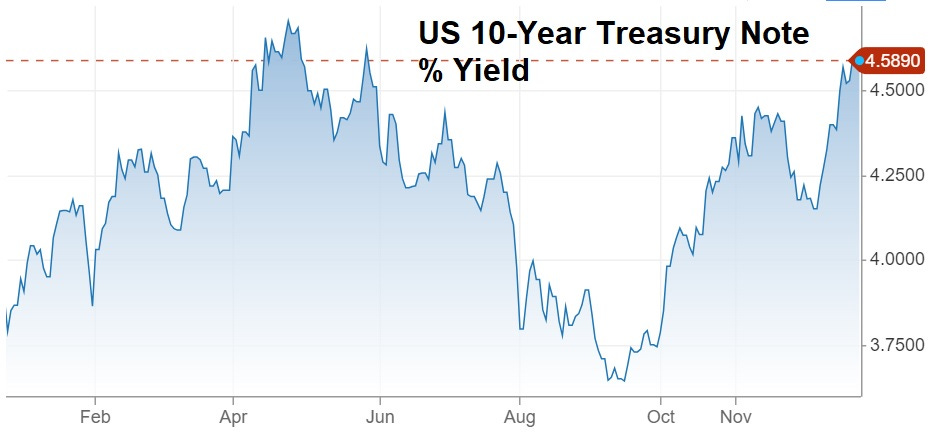

The 10-year Treasury yield briefly touched 4.6% yesterday. That translates into 7% mortgages and higher rates on a whole range of other loans.

Meanwhile, the major stock market indexes have risen dramatically in the past couple of months. This seems incongruous, but historically it’s both normal and ominous.

Here’s a post from mid-2023 putting today’s a…